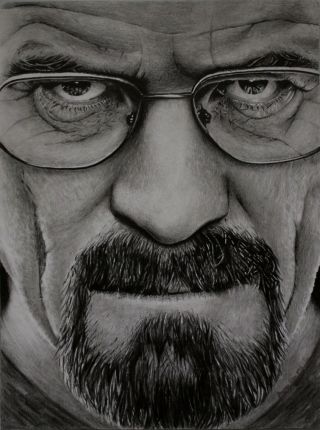

Vince Gilligan, creator of Breaking Bad, said that his goal with Walter White was to turn Mr. Chips into Scarface. Take a regular person, like you—assume you’re regular for a second—and then make you nice and evil, like a witch in a gingerbread house. Is that really even possible? Could you become another Walter White?

I’m inclined to believe that most of us still think some people are good and some people are bad, and never the twain shall meet. Despite the lessons we learned from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, we still think that good and evil belong in different people. Walter clearly shows that it doesn’t. And he demonstrates this with so many good psychological reasons—reasons that experimental psychologists observe in ‘normal’ people on a daily basis.

What are these reasons and do they apply to you? See for yourself.

Reason 1: Anyone can become a killer

David Buss wrote a book a few years ago called “The Murderer Next Door: Why the Mind is Designed to Kill.” One of the central points of this book is that, not only do the majority of us consider killing other people in our lives (more than 80% of both sexes), but—if the external conditions are right—many of us actually do. We do it out of jealousy, rage, self-defense, greed, and revenge

Moreover, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to observe that wars kill people, nor are they necessarily the domain of the insane. When moral boundaries are drawn differently, a lot of people comply by engaging in behavior they otherwise wouldn’t. Including murder. From draftees to presidents. Consider that Obama probably never thought taking someone’s life would become part of his political career, but indeed, it has. And as difficult a decision as it was to make, I imagine many of us would have done the same. So consider this step one on your way to becoming Walter White.

Reason 2: Believing you're a victim makes you more likely to commit a crime

Many studies have shown that social inequality drives up crime rates. When the poor and the rich live near one another, laws get broken. Social comparison is usually blamed—and it’s a nasty thing. Studies find that kids will take less to avoid others having more. Offer a child the choice between having three candies if his sister can have four, versus having two candies if his sister gets one and see what happens. Moreover, people are often unhappier if promotions don't seem to follow easy to understand rules, even when they’re promoted more rapidly as a result. The trouble is that in almost any situation, there is almost always someone who is better off than you. So if you think you're a victim of unfair treatment because other people have it better than you, consider this step two on your way to becoming a bad guy.

But there's more to it than that. A lot of people blame Walter's bad behavior on his sad situation: his cancer, his humiliating job(s), his family life, and his regrettable relationships with past co-workers. Whether this is worse than what other non-criminals have to deal with is beside the point, the question is about what Walter believes. And he does believe he is a victim, at least in the beginning. The problem with believing you have no control over your life (that you’re a victim) is that it increases your chances of being a jerk. Several recent studies have shown that being led to disbelieve in your ability to control your own fate (i.e., your free will) directly increases the chances that you will be aggressive, cheat, and fail to help others.

Reason 3: Thinking you have nothing left to lose is not good for your health

The problem with thinking you have nothing left to lose is that you start to take risks you otherwise wouldn’t. This is sometimes called risk sensitivity, which basically says that it makes sense to take risks when you're likely to lose if you don’t. This explains the end of countless football and hockey games. Moreover, it's built fairly deeply into our DNA. Animals will often choose risky food schedules with rare large gains when on a diet otherwise insufficient to sustain life, whereas animals with enough food prefer certain small gains to uncertain large gains. Yes, even animals appear to understand the logic of the hail mary pass.

The same general logic has been used to explain suicide bombers. Studies on the statistics of suicide bombers find that most suicide bombers are male, unmarried, and are often from larger than average families. Mix that with life in a polygynous environment where employment is low and reproductive prospects (i.e., marriage) are dependent on money (and not having to share it with your brothers). Now compare the alternatives between being an evolutionary black hole and an eternity with virgins and reported monetary rewards for your family. Though I don't recommend it, maybe turning yourself into a religious martyr doesn't sound so bad after all.

Reason 4: Pretending to be bad is a gateway drug to the real thing

Can pretending to be a ruthless drug dealer make you a ruthless drug dealer? There are many forms of evidence to suggest the answer is yes. Obviously, it's hard to collect data on pretend drug dealers, but there is a considerable history of collecting data on people pretending to do things. Following on a study by Laird (1974), many people have investigated the effects of 'fake' smiles, which appear to make us happier, more likely to perceive humor in things, and even lead to heart benefits.

But similar effects can be found on the darker side. Zimbardo's prison experiment found that asking people to pretend to be prison guards led them to become rather unpleasant individuals--especially if you were a prisoner. But we have even better data now. One of the biggest sources of this data is on people playing violent video games (Jesse even shows us how it works). Here, the evidence is enough to explain even the daily shootings in the good old USA. As far back as 1995, when the enemy in video games was represented by no more than a few pixels, children became more aggressive to real people and real objects following violent video game play. Since then, meta-analyses of hundreds of data sets show a small but consistent positive effect of violent video games on aggression. Multiply this by the number of people actually playing these games, and it becomes clear that even if violent video games led to real violence in less than one in a million game players, you'd still hear about it several times a day in the news.

Reason 5: Costly mistakes can make us do stupid things

Shouldn't failure have taught Walter White a lesson? Hardly. Failure is not so predictable. Moreover, costly mistakes can be some of the hardest to learn from, because they are the ones we feel most obligated to rationalize. One of the best-researched decision making fallacies we know of is the sunk cost fallacy. Sometimes it’s called arguments from waste. "We can't stop now, that would be a huge waste!" Governments commit this fallacy when they continue with losing wars, often arguing that we cannot let soldiers to have died in vain. Basketball coaches do it when they continue to give greater playing time to higher draft picks even when they have sub-par performance. Indeed, studies show that companies do it routinely, by investing in failing product lines. Regular folks like you and me often do it to save face, because obviously we aren't stupid—we just need to give our bad decisions a little more support to help them mature into the good decisions we know they truly are.

One could argue that after Walter's initial decision to cook meth, the sunk cost fallacy does a lot of the work of bringing his professional meth career to its peak performance. He's constantly cleaning up after himself. Indeed, Walter frequently makes arguments from waste. How could so much cost have led to so little gain? Clearly the only solution is to cook more meth, kill the 'last' person standing in the way, etc. Walter is making this argument every time we hear him say something like "this is the last time," which he seems to say about once every other episode.

Beware, sunk costs are probably involved in all kinds of unfortunate things, from unhappy marriages to sticking with ailing vehicles to that unfortunate temptation to kill innocent witnesses. If you're going to be a criminal, it would be better if you just tried harder to avoid being seen in the first place.

Reason 6: Crime has all the makings of an addiction

The statistics on crime suggest that, in at least some ways, it's just like eating chips. You can't stop with just one. In a report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) on convicted criminals, the average number of crimes initially committed by these individuals was 13 per convicted criminal. Though I'm sure a lot of Gus Frings bring the average up for the rest of us.

Nonetheless, crime looks in many respects like an incurable disease with occasional flare-ups. The BJS report shows that following release from prison, approximately 67% of the criminals in the study were rearrested for a new crime within 3 years. The rearrest rate is highest for perpetrators of property crimes--with about a 70% reincarceration rate. Among those convicted of homicide, the reincarceration rate was lower, at about 40%—I guess that's a bright side. Unfortunately, these individuals are convicted of homicide again at a rate about 53 times higher than the rest of the adult population. That’s not exactly the same as eating a whole bag of chips, but it certainly puts you in the right risk group.

A Brief Respite

You'll be happy to know that terminal illness doesn't appear to turn people into the criminally ill. I looked long and hard for evidence that it could, but found basically nothing. You can imagine this is hard data to collect. People with terminal illness have lots of reasons for not going out and committing crimes, including the simple fact that they probably don't feel well. So the data here is hardly compelling and is notable mainly for its absence.

Nonetheless, the other reasons above hopefully point out plenty of great ways to turn your life into a shambles without even thinking about it. You don't have to be born bad to turn bad. You just have to apply yourself.

Thomas Hills on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment